l

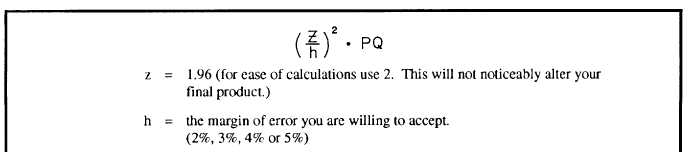

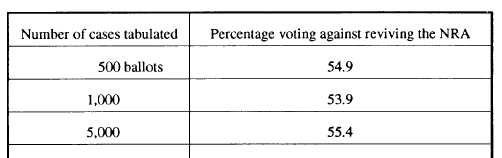

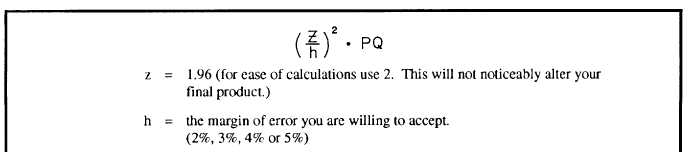

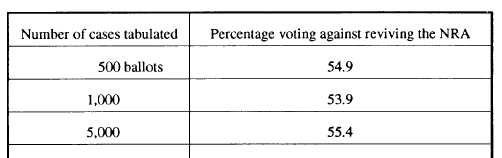

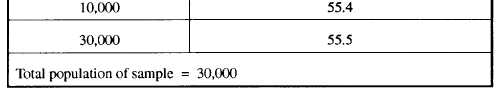

Figure 9-2.—Sample size increase vs. accuracy.

What are the time and cost constraints? Do

you have the time, manpower and money to

accomplish whatever survey project you are

attempting? This is important. Set deadlines and

give specific job assignments or else piles of

survey junk may end up stashed in someone’s

desk drawer.

SAMPLE SELECTION

How large should a sample be from any given

population? This question takes us into the mathematics

of probability. Do not worry, you will not have to

understand the statistics behind national surveys

produced by the likes of George Gallup. But perhaps a

quote from Mr. Gallup might help put the question of

sample size in perspective. “Both experience and

statistical theory point to the conclusion that no major

poll in the history of this country ever went wrong

because too few persons were reached.”

Gallup conducted a number of experiments on the

effects of sample size. In 1936, he used 30,000 ballots

to ask the question: “Would you like to see the National

Recovery Act (NRA) revived?” The first 500 ballots

showed a “no” vote of 54.9 percent. The complete

sample of 30,000 ballots returned a “no” vote of 55.5

percent. In other words, the addition of 29,500 ballots

to the first 500 ballots only made a difference of 0.6

percent. (See fig. 9-2.)

Through the mathematics of probability, we know

there is a real but unknown distribution of all possible

answers to a question. If we then know that our sample

is random (meaning that every person in our audience

is just as likely to get a survey as any other person) and

that our techniques are capable of obtaining a reliable

response (without bias) from each person, we will be

able to tell how representative the responses are.

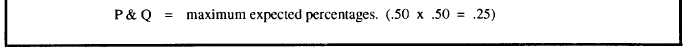

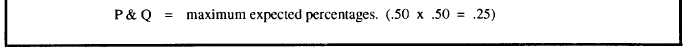

For the purposes of this chapter, the Sociology

Department at the University of West Florida supplied

a quick and easy formula often used in social science

research. It is shown in figure 9-3.

Figure 9-3.—Sample size formula.

9-6